|

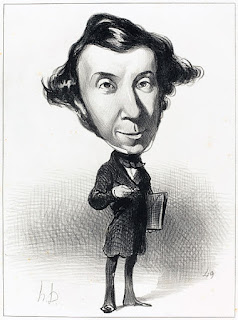

| Caricature of Alexis de Tocqueville by Honoré Daumier (1849). |

By Keith Tidman

Recently, Joe Biden asserted that ‘democracy doesn’t happen by accident. We have to defend it, fight for it, strengthen it, renew it’. And so, America’s president, along with leaders from over a hundred other similarly minded democratic countries, held the first of two summits, to tackle the ‘greatest threats faced by democracies today’.

Other thought leaders have weighed in, even calling democracy ‘fragile’. But is democracy really on its heels? I don’t think so; democracy is stouter than it’s given credit for, able to fend off prodigious threats. And here, in my view, are some reasons why.

First, let’s briefly turn to America’s founding fathers: James Madison famously said that ‘If men were angels, no government would be necessary’. A true-enough maxim, which led to establishing the United States’ particular form of national governance: a democratic republic. With ‘inalienable’, natural rights.

Many aspects of democracy helped to define the constitutional and moral character of Madison’s new nation. But few factors rise to the level of unencumbered ideas.

Ideas compose the pillar that binds together democracies, standing alongside those other worthy pillars: voting rights, free and fair elections, rule of law, human-rights advocacy, free press, power vested in people, self-determination, religious choice, peaceful protest, individual agency, freedom of assembly, petition of the government, and protection of minority voices, among others.

Ideas are the pillar that keeps democracy resilient and rooted, on which its norms are based. They constitute a gateway to progress. Democracy allows for the unhindered flow of different social and political philosophies, in intellectual competition. Ideas flourish or wither by virtue of their content and persuasion. Democracy allows its citizens to choose which ideas frame the standards of society through debate and the willingness to subject ideas to inspection and criticism. Litmus tests of ideas’ rigour. Debate thereby inspires policy, which in turn inspires social change.

Sure, democracy can be messy and noisy. Yet, democracies do not, and should not, fear ideas as a result. The fear of ideas is debilitating and more deleterious than the content of ideas, even in the presence of disinformation aimed to cleave society. Countenancing opposing, even hard-to-swallow points of view ought to be how the seeds of policy sprout. Tolerance in competition, while sieving out the most antithetical to the ideals of society, helps to lubricate the political positions of true leaders.

Democracy makes sure that ideas are not just a matter for the academy, but for everyone. A notion that heeds Thomas Jefferson’s observation that ‘Government is the strongest of which every man feels himself a part’. Inclusivity is thus paramount; exclusivity aims to trivialize the force-multiplying power of common, shared interests, and in the process risks polarizing.

Admittedly, these days our airwaves and social media are rife with hand-wringing over the crisis or outrage of the moment. There’s plenty of self-righteousness. On the domestic front, people stormed the Capitol building just over a year ago, unsuccessfully attempting to interrupt the peaceful handover of presidential power. Extremists of various ideological vintage shadow the nation. Yet, it’s easy to forget that the nation has been immersed in such roiling politics and social hostilities earlier in its history. There’s a familiarity. All the while, powerful foreign antagonists challenge America’s role as the beacon of democracy. The leaders of authoritarian, ultranationalistic regimes delight in poking their thumb into America’s and Europe’s eye.

Lessons of what not to do come from these authoritarian regimes. Their first rule is not to brook objection to viewpoints prescribed by the monopolistic leader. Opinions that run counter to regimes’ authorised ‘truth’ — shades of Orwell’s 1984 — threaten authoritarians’ survival. They race to erase history, to control the narrative. Insecurities simmer. If the chestnut ‘existential crisis’ applies anywhere, it’s there — in autocrats’ insecurities — to be exploited. Yet, they’re aware that ‘People rarely take to the streets demanding autocracy’, as recently pointed out by the former Danish prime minister, Anders Fogh Rasmussen. Contrarianism menaces the authoritarians’ laser focus on power and control: their imposition of will.

The free flow of ideas is democracy’s nursery of innovation. The constructive exchange of opinions is essential for testing hypotheses, to determine which ideas are refutable or confirmable, and thus discarded or kept. Ideas are commanding; they are democracy’s bulwark against the paternalism and disingenuousness of hollowed-out constitutional rights, which have been autocracies’ fraudulent claim to mirror democracies’ bills of rights.

All this leads to the cautionary words of the nineteenth-century political philosopher and statesman Alexis de Tocqueville:

‘…that men may reach a point where they look at every new theory as a danger, every innovation as a toilsome trouble, every social advance as a first step toward revolution, and that they may absolutely refuse to move at all’.

5 comments:

I would suggest that information is the bulwark of democracy, because, through information, one gets a fix on how one’s world is ordered. Ideas do not necessarily have an eye for how the world is ordered. In fact some ideas are seriously counterproductive.

Thank you, Thomas, for your thoughts distinguishing between ideas and information in context of this discussion about democracy.

Freely flowing ideas — or, as you prefer, freely flowing information — are antithetical to the vitality of authoritarianism.

One of the top-shelf things that autocrats covet is to control the narrative and to define their version of truth, no matter how untrue their truth; it’s about power and control, not metrics of reality.

Misguidedly, the view of democracy as fragile or brittle, and facing existential crises — unconquerable challenges, if you will — is the favored position among opinion writers these days, and becoming more so.

All quite fashionable, in a Paris intellectual café sort of way. No matter how erroneous. (Though I’d partially concede this Orwellian nugget: ‘who controls the past controls the future’.)

I see greater risks and headwinds for social and political progress in autocracies that, in a ‘1984’ way, insist to their publics that ‘war is peace’ and ‘freedom is slavery’ -- and that don’t breezily make room for citizens who might disagree.

Contrarian viewpoints aren’t brooked.

It’s no surprise, but I'd take democracy, with whatever blemishes it might exhibit through history, over the ham-fisted regimes transitorily bubbling up here and there.

Thank you Keith for your strong expression of and confidence in a democracy of virtuous ideas able to withstand all challenges.

I'm sure that you and Pi readers are well aware of Platonian discussions and ideas on democracy. Given the present day "Trump/GOP Cult" (my own bias clearly evident), I must agree with Plato and his description of how, in a free wheeling democracy of ideas, power seeking individuals lacking personal skills and morals can be motivated by personal gain and can become highly corruptible, eventually leading to tyranny prioritizing wealth and property accumulation over virtue.

While the idea that the 2020 Presidential election was corrupted and stolen from Trump continues to wash over our democracy, it is difficult for me to be optimistic that tyranny will not emerge as Plato predicted 2500 years ago.

I agree with you that mere democratic blemishes are far acceptable to tyranny and autocracy but the lust for power based upon monetary greed and its control of our democracy is very obvious today.

My view, John, is that societies cannot survive if they are too far out of touch with (international) social or environmental reality. For this reason, no authoritarian or tyrannical regime will succeed in the long run. They will come up against limitations which are larger than themselves. Rome ran out of resources. Iran almost lost too much favour to survive. The prioritisation of wealth and property accumulation, as you call it, has almost run out of habitat. Cyril of Jerusalem, in the fourth century AD, held that even the Antichrist would succeed for only three-and-a-half years, still a widely held belief today. I haven’t had anyone oppose this argument, except to say that some authoritarian or tyrannical regimes have lasted a lot longer than three-and-a-half years, and too long for their inevitable demise to be a comfort.

Thanks Thomas, it is my fervent hope that you are correct about the ultimate curve of human interaction/existence is toward freedom and respect for our fellow man and their views, ultimately peaceful equality of all respectful of all, not autocracy or tyranny. Whether this can be achieved by democracy is doubtful.

Of course our discussion can go on to the next extinction but it is my view that only a one world government can achieve this lofty goal. Perhaps a human developed benevolent artificial intelligence with a machine take over could extend human existence; I prefer a benevolent extraterrestrial visitation.

Post a Comment