Today, the politics of Americans – and many other countries too, including the U.K – with respect to Israel is characterised by three things. Prejudice against Arabs - who are seen as various kinds of “terrorist”; ignorance and indifference to the history of the region. However, American politics add in one other ingredient, and a most dangerous one too, which is an irrational conviction that the Bible predicts the Second Coming of the Messiah – but only once the Holy Land is reunited under Israeli control. It has even been suggested that Joe Biden is part of this evangelical cult, though I have no way of knowing if this rumour is true. What I do know is that this ridiculous and irrational view has considerable influence on both Democrat and Republican parties. It feeds into a political consensus that, one way or bloody another, Palestine needs to become “Israel”.

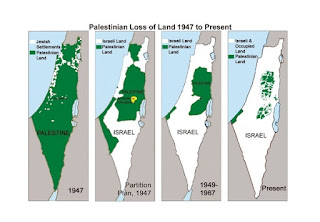

Nonetheless, in November 1947, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution partitioning Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab (with Jerusalem under UN administration). When, understandably, the Arab world rejected the plan, Jewish militias launched attacks against Palestinian towns and villages, forcing tens of thousands to flee. The situation escalated into a full-blown war in 1948. The result of this war was the permanent displacement of more than half of the Palestinian population.

Today, most of the inhabitants of Gaza are refugees or descendants of refugees from the 1948 Nakba and the 1967 war, and more than half are under the age of 18. Apart from the tragedy of forcibly displacing children, attempts to blame the inhabitants of Gaza for either “voting for” Hamas or not resisting them are hollow given this age distribution.

Today too, due to Israel’s siege of Gaza, the majority of Palestinians there no longer have access to basic needs such as healthcare, water, sanitation services, and electricity. Prior to the siege, their situation was already pretty desperate: according to the UN, 63 percent of the population was dependent on international aid; 80 percent lived in poverty and 95 percent did not have access to clean water.

Alas, many American voters have been encouraged to feel indifference to Palestinian suffering for decades, and instead have passively accepted an alternative reality in which the Jewish people not only there - but worldwide - are a persecuted but courageous minority. Never mind that nearly six million Americans are Jewish and live pretty safely there…

The bottom line then is that, in the normal way, there is NO political price to be paid by the Democrats for supporting the Israeli government in its latest, murderous expansion of “Jewish areas”. However, this time, I actually think is NOT normal.

The catch is, despite Biden's "unconditional" support, Israel knows the Palestinians won't conveniently flee abroad (despite so many being killed at the moment, with highly publicise strategies of cutting off water and bombing hospitals) so its strategy becomes one of just killing. But Gaza alone contains some 600 000 people - mostly children. If they won’t flee, then they need to be killed. After all, Gaza was already a kind of prison. It will be hard to square that circle.

When I was younger, I remember meeting some of the "IDF heroes" of the last war - certainly they fought at a significant disadvantage against well-armed foes. Could it be today that the 360 000 reservists now begin to doubt their commanders? I think it is possible. However, If not, they will soon find themselves wading through civilian bodies in the rubble of Palestinian homes.

But back to a question posed recently on Quora will Biden pay a price for his indifference to the plight of millions of Palestinians? No, in the short term, I don’t see Biden or anyone else paying a price for this. However, in the longer term – indeed maybe as soon as within a few months – I think things will look very different At which point, either Israel corrects itself (as Netanyahu represents only a small minority) – or history will do it for them.

Further reading on Palestine

https://visualizingpalestine.org/visuals/http-visualizingpalestine-org-visuals-shrinking-palestine-static

https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/rpal20/collections/GazaTwoDecades