|

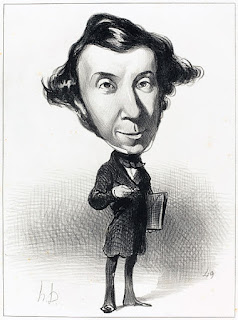

| Caricature of Alexis de Tocqueville by Honoré Daumier (1849). |

By Keith Tidman

Recently, Joe Biden asserted that ‘democracy doesn’t happen by accident. We have to defend it, fight for it, strengthen it, renew it’. And so, America’s president, along with leaders from over a hundred other similarly minded democratic countries, held the first of two summits, to tackle the ‘greatest threats faced by democracies today’.

Other thought leaders have weighed in, even calling democracy ‘fragile’. But is democracy really on its heels? I don’t think so; democracy is stouter than it’s given credit for, able to fend off prodigious threats. And here, in my view, are some reasons why.

First, let’s briefly turn to America’s founding fathers: James Madison famously said that ‘If men were angels, no government would be necessary’. A true-enough maxim, which led to establishing the United States’ particular form of national governance: a democratic republic. With ‘inalienable’, natural rights.

Many aspects of democracy helped to define the constitutional and moral character of Madison’s new nation. But few factors rise to the level of unencumbered ideas.

Ideas compose the pillar that binds together democracies, standing alongside those other worthy pillars: voting rights, free and fair elections, rule of law, human-rights advocacy, free press, power vested in people, self-determination, religious choice, peaceful protest, individual agency, freedom of assembly, petition of the government, and protection of minority voices, among others.

Ideas are the pillar that keeps democracy resilient and rooted, on which its norms are based. They constitute a gateway to progress. Democracy allows for the unhindered flow of different social and political philosophies, in intellectual competition. Ideas flourish or wither by virtue of their content and persuasion. Democracy allows its citizens to choose which ideas frame the standards of society through debate and the willingness to subject ideas to inspection and criticism. Litmus tests of ideas’ rigour. Debate thereby inspires policy, which in turn inspires social change.

Sure, democracy can be messy and noisy. Yet, democracies do not, and should not, fear ideas as a result. The fear of ideas is debilitating and more deleterious than the content of ideas, even in the presence of disinformation aimed to cleave society. Countenancing opposing, even hard-to-swallow points of view ought to be how the seeds of policy sprout. Tolerance in competition, while sieving out the most antithetical to the ideals of society, helps to lubricate the political positions of true leaders.

Democracy makes sure that ideas are not just a matter for the academy, but for everyone. A notion that heeds Thomas Jefferson’s observation that ‘Government is the strongest of which every man feels himself a part’. Inclusivity is thus paramount; exclusivity aims to trivialize the force-multiplying power of common, shared interests, and in the process risks polarizing.

Admittedly, these days our airwaves and social media are rife with hand-wringing over the crisis or outrage of the moment. There’s plenty of self-righteousness. On the domestic front, people stormed the Capitol building just over a year ago, unsuccessfully attempting to interrupt the peaceful handover of presidential power. Extremists of various ideological vintage shadow the nation. Yet, it’s easy to forget that the nation has been immersed in such roiling politics and social hostilities earlier in its history. There’s a familiarity. All the while, powerful foreign antagonists challenge America’s role as the beacon of democracy. The leaders of authoritarian, ultranationalistic regimes delight in poking their thumb into America’s and Europe’s eye.

Lessons of what not to do come from these authoritarian regimes. Their first rule is not to brook objection to viewpoints prescribed by the monopolistic leader. Opinions that run counter to regimes’ authorised ‘truth’ — shades of Orwell’s 1984 — threaten authoritarians’ survival. They race to erase history, to control the narrative. Insecurities simmer. If the chestnut ‘existential crisis’ applies anywhere, it’s there — in autocrats’ insecurities — to be exploited. Yet, they’re aware that ‘People rarely take to the streets demanding autocracy’, as recently pointed out by the former Danish prime minister, Anders Fogh Rasmussen. Contrarianism menaces the authoritarians’ laser focus on power and control: their imposition of will.

The free flow of ideas is democracy’s nursery of innovation. The constructive exchange of opinions is essential for testing hypotheses, to determine which ideas are refutable or confirmable, and thus discarded or kept. Ideas are commanding; they are democracy’s bulwark against the paternalism and disingenuousness of hollowed-out constitutional rights, which have been autocracies’ fraudulent claim to mirror democracies’ bills of rights.

All this leads to the cautionary words of the nineteenth-century political philosopher and statesman Alexis de Tocqueville:

‘…that men may reach a point where they look at every new theory as a danger, every innovation as a toilsome trouble, every social advance as a first step toward revolution, and that they may absolutely refuse to move at all’.